Hydrocarbon activity spans more than a century in Greece; yet the country remains one of the least explored nations in the East Mediterranean region.

Excitement about the country’s emergence as a significant player in the regional hydrocarbons stage has felt like a roller coaster, mainly rekindling after the success stories experienced by neighbours. A good example of that was the impressive comeback of Greece in 2011 after a 15-year absence from the global exploration and production scene, following the discoveries made in the eastern Mediterranean that were perceived to transform paupers into princes.

The comeback at that time was realised through a number of developments, including the introduction of a new legal and regulatory framework for hydrocarbon exploration, as well as the establishment of the state-owned Hellenic Hydrocarbon Resources Management (HHRM) in charge of managing the rights of the State relating to the exploration and exploitation. In 2014, for the first time after almost two decades, the government signed concession agreements in western Greece. These were followed by an international round in 2015 and subsequent "Open Door” rounds, resulting in the award of more concessions in the areas of the Ionian Sea and Crete. The involvement of oil majors in these concessions, namely Total, ExxonMobil and Repsol, was perceived as a good omen for the best to come for Greece.

In particular, big expectations were spawned over that time that Greece sits on massive untapped resources of oil and gas, which could generate billions of dollars, enough to pay out the country’s debt and help it exit from the crisis. Although the narrative built around it was unrealistic, this would still have potential for a tangible positive impact; however, on a longer timeline and a lower scale.

Despite all the promise, though, not a single well has been drilled since 2011, when Greece decided to revive its oil sector. The Prinos oilfield, which has been in operation since 1981, remains Greece’s only oil-producing asset as of today.

A bumpy future

In the meantime, the oil and gas industry has endured some fundamental changes over the last few years, which have dictated a murkier outlook for the global upstream investment. Naturally, that has raised the question of whether Greece has missed the opportunity to untap its true natural resources potential, especially in the current lower oil price environment and the continuing proliferation of oil majors shifting their interest towards greener energy.

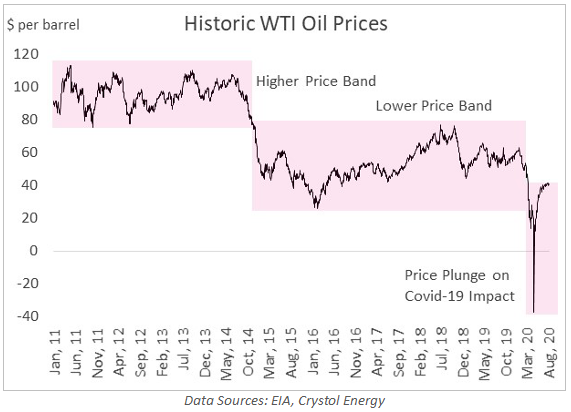

Following a relatively stable and high oil price environment, with prices trading on average at about $100 per barrel between 2011 and 2014, the oil sector has been in turmoil since. The oil price plunge in 2014, mainly due to the shale revolution and its persistence, which required OPEC to assemble the largest alliance in the oil history to agree on coordinated production cuts in order to stabilise the market, had a substantial impact on oil majors’ upstream spending plans. Although companies had already started to reduce exploration investment even before the 2014 oil price collapse, the downturn accelerated the trend, with the spending in the sector almost halving between 2014 and 2018, according to the IEA.

Now, only a couple of years later, investment in the oil and gas sector has been hit with an even greater shock. The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has prompted a historic destruction of oil demand, with the world’s biggest oil and gas firms announcing, one after the other, substantial cost-cutting measures. Slashing exploration budgets is among the companies’ imperative actions in their effort to control finances, a fact that is expected to culminate in a stiffer competition for global upstream investment.

The novel pandemic, though, seems to have accelerated another trend, that of oil majors to make their businesses more agile by branching out into new sectors and low-carbon technologies and committing themselves to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. While oil and gas companies proceed into exploration spending cuts, clean-energy investment plans seem to remain intact – at least for now – adding another dimension to the existing competition, this time from renewables.

A narrowing window

Despite the murkier outlook, not all investment is expected to dry up for the global upstream industry. The oil and gas sector is used to work in a cyclical fashion and has experienced dramatic cyclical swings in the past. For operators, the current market conditions could be a good opportunity to commit capital budgets as prices in the upstream supply chain are at a historic low. However, even under the scenario of a tougher crisis this time, driven by significant efficiency gains, the net zero movement and the Covid-19 implications, that will see the role of oil shrinking, it is projected that oil remains the dominant fuel in the foreseeable future, while natural gas continues gaining a larger share in the global energy mix, playing an important role in the decarbonisation journey, especially in the EU market.

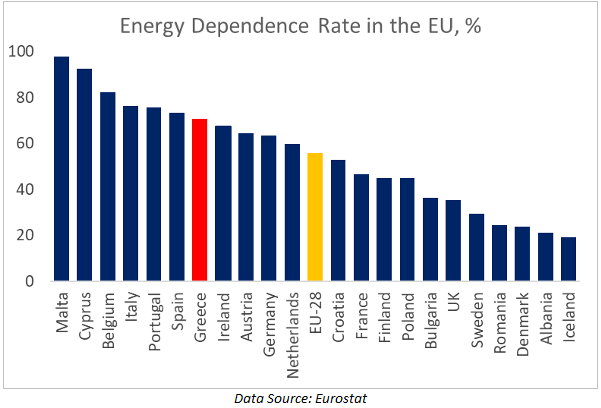

On the latter, Greece has a comparative advantage, thanks to its proximity to Europe. The country is well placed to commercialise any of its gas resources by providing the EU with an alternative supply path toward its plans for both diversification and decarbonisation. Any oil and gas resources could also, undoubtedly, supply the inland market in Greece, assisting the country in the reduction of its energy dependence, which stands at 70% compared to the EU-28 average of 55%, based on Eurostat data, as well as its own decarbonisation process.

While Greece has successfully managed to attract the interest of big oil and gas players, despite the adverse environment caused by lower oil prices, it seems that renewables, for which the country has great potential, have somehow downgraded the interest in hydrocarbons as the government’s priorities turn to the wider development of green energy. That was emphasised through the submission of the 10-year National Plan for Energy and Climate (NEPC) to the EU Commission in December 2019, which not only outlined the government’s commitment to the bloc’s wider pledge for transition to a green economy, but more importantly, it noted the ambitious upgrade of renewables in the country’s energy mix to 35% of total energy consumption by 2030, up from about 13% currently.

However, acknowledging the fact that conventional oil and gas projects typically require four to seven years to be developed, that leaves a time scale of about two decades before the profitability of such projects gets questioned. If Greece is serious enough about ‘exploiting’ the economic benefits gained through the exploration and production of hydrocarbons and converting the country to an energy hub, it will need to act fast.

There have recently been a few developments which could predispose the government’s intention to move towards that direction, including the revamp of HHMR, the boundary delineation agreements with Italy and Egypt, as well as the Energy Ministry’s approval of the strategic environmental impact study for south of Crete that will pave the way for tendering licenses, but still a stronger determination and reaction are needed.

With any exposure built by oil and gas companies over the following years focusing on the best only resource opportunities, Greece needs to show strong momentum, as well as remain attractive enough to compete with other projects across the world. That would imply expediting hydrocarbon exploration by eliminating any bureaucratic hurdles and ensuring that the terms on offer reflect the current realities of the market. That of course, makes the government’s task even harder as it will still need to safeguard the realisation of its committed energy and climate goals over the next decade.