In the endeavor to prevent a devastating climate crisis, there is an escalating demand for Critical Raw Minerals (CRMs). Minerals serve as essential components for clean energy technologies, such as wind turbines, batteries, and electricity grids.1 As countries take steps to diminish their carbon footprint, it's imperative to implement practices that ensure the resilience and security of energy systems. The growing importance of minerals in decarbonizing energy systems underscores the necessity for policymakers to broaden their perspectives and contemplate potential new vulnerabilities.2

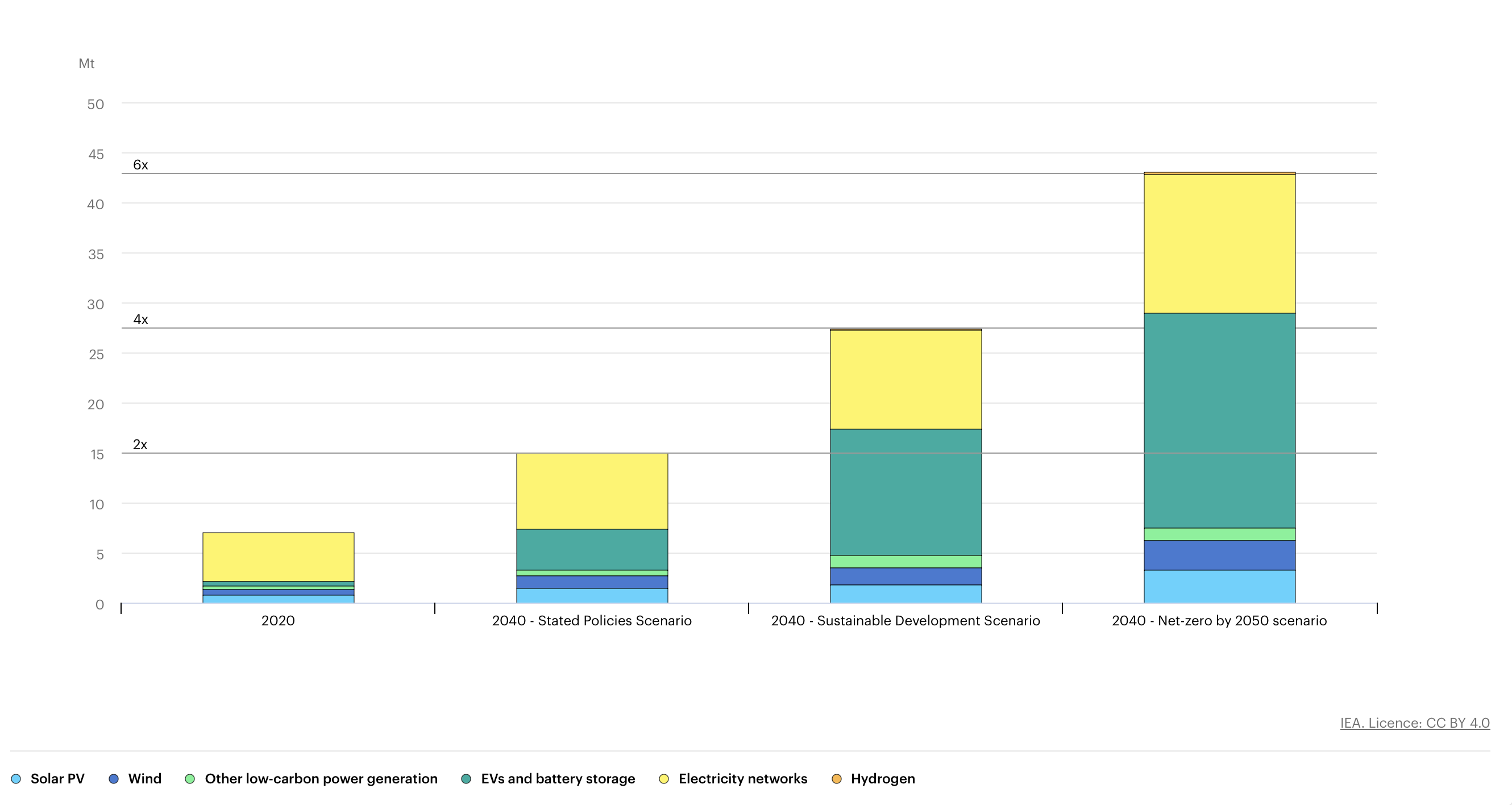

Total demand for minerals intended for green technologies by scenario, 2020 compared to 2040. Source: IEA (2021)

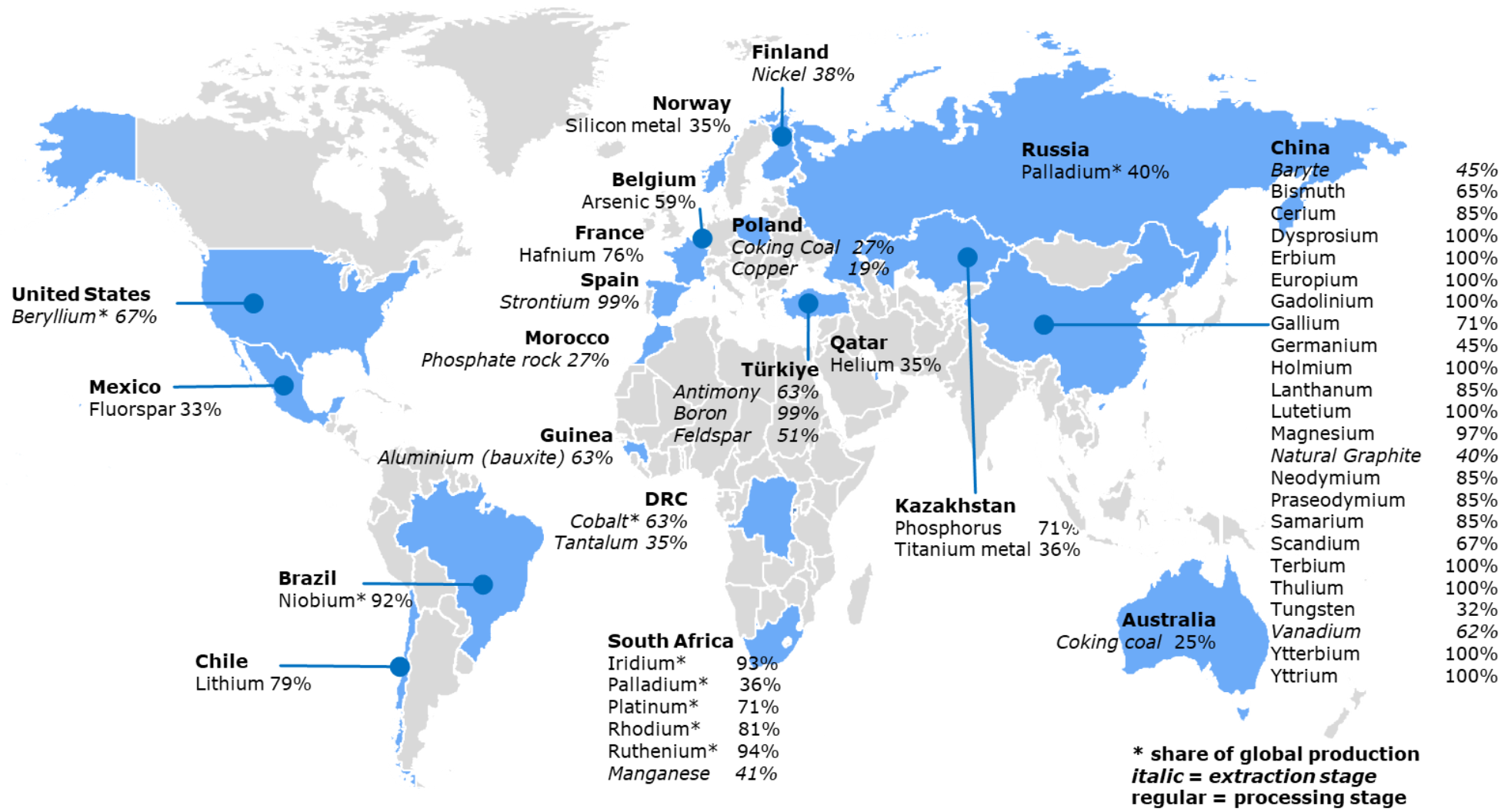

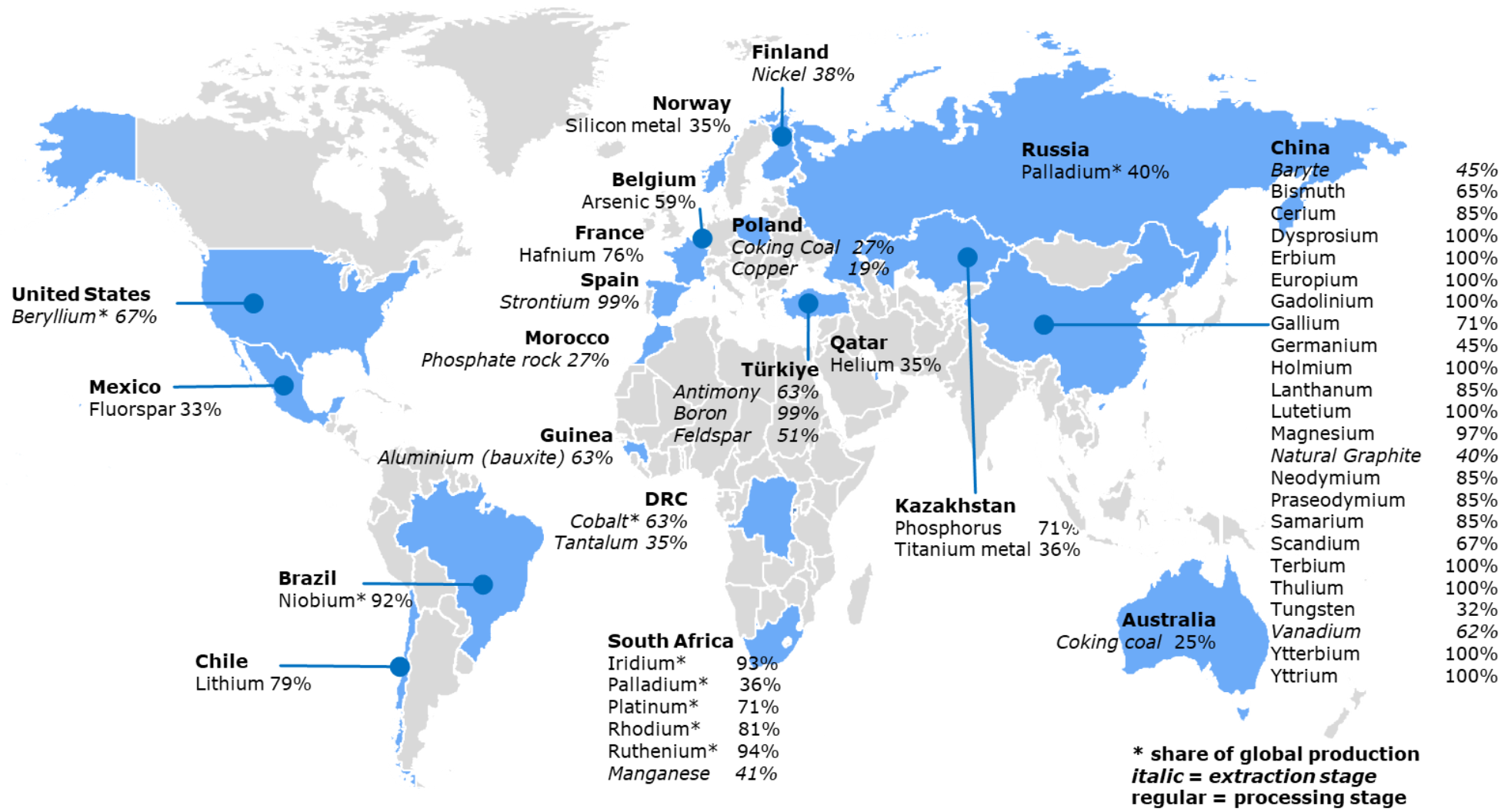

This issue is certainly not absent from the European agenda, as the EU’s supplies in CRMs are primarily sourced outside its borders, while its self-sufficiency is unattainable. Nowadays, EU is solely reliant on China for certain CRMs, with China providing 100% of its supply of heavy rare earth elements.3 This dependency is perceived as a significant economic threat, as it allows China to pull the strings of the market. Consequent geopolitical risks and supply disruptions further exacerbate the situation, prompting the EU to take up the formidable challenge of achieving strategically independent supply chains. In this context, the annihilation of supplies from China does not sound realistic, with the Union's objective focusing on building a diversified portfolio, while maintaining good relations with its Chinese partners and avoiding overreliance on them.4

In addition to seeking alternative international partners, the EU is determined to start extracting its own mineral wealth. Greece stands firmly behind the EU’s drive for strategic autonomy and is poised to play a pivotal role in this endeavor.5 With plenty ore deposits in its subsoil, Greece emerges as one of the EU’s member-states with the greatest capacity to supply CRs in the foreseeable future.6

Background

The sufficient supply of critical minerals is inexctricably linked to meeting the ambitious goals set forth in the Paris Agreement and realizing the green energy transition. Minerals such as copper, lithium, nickel, and cobalt are indispensable in numerous expanding green technologies, ranging from wind turbines and solar panels to electric vehicles. According to the IEA, the demand for these minerals could skyrocket sixfold by 2050, with their market value anticipated to soar to an astounding US$400 billion, eclipsing the total value of coal extractions in 2020.7

The European Union stands at the forefront of endeavors to combat climate change by rapidly deploying clean energy technologies. The EU's initiative is underscored by an ever-expanding series of projects geared towards the construction of wind turbines, electrolytes and electric vehicle (EV) batteries. However, amidst the EU's efforts to bolster its clean energy manufacturing capacity, persistent dependence on imports of critical materials remains a pressing concern among multiple Member States.8

In particular, the EU is facing a stranglehold on critical minerals from China, as it supplies four-fifths of the European solar panels,9 and 90% of its rare earth permanent magnets and battery-grade lithium needs.10 The COVID-19 pandemic and Russia's aggressive war against Ukraine exposed the severe consequences of heavily depending on a signle supplier,11 while centralizing CRMs processing, refining, and manufacturing in one location can also appear risky, as trade routes can be disrupted due to military conflicts, such as those in the Taiwan Strait.12 Furthermore, the Suez Canal blockage in 2021 and the Read Sea conflict in late 202313 further emphasize the costs associated with regional or individual dependencies for Europe and the overall global economy.14

To mitigate future shocks and eliminate the risk of "geo-economic fragmentation”,15 the EU has been implementing legislation aiming to enhance its security of supplies and bolster its resilience against various geopolitical risks, through initiatives such as the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA).16

In 2022, EU Commission’s President, Ursula von der Leyen, introduced the concept of the CRMA, followed by the proposal for a Regulation on March 16, 2023, as part of the Green Deal Industrial Plan. The CRMA seeks to establish a regulatory framework enhancing every facet of the EU’s CRMs value chain, broaden the region’s imports to mitigate strategic dependencies, expand Europe’s capacity to monitor and address risks connceted to disruptions to the supply of CRMs, while improving circularity and sustainable practices.17

Implications of Chinese Trade Decoupling

At this point, though, a critical question arises: Αre the CRMA benchmarks achievable in order to meet the EU’s decarbonization and strategic independence ambitions? The CRMA proposes a 10% target for EU sourcing, but it’s found that 7 out of the 18 listed CRMs fail to satisfy this requirement at the mining stage, given that the EU sources at least 94% of them from third counties. In addition, 21 out of 24 materials fall short of the requirement that at least 40% of the EU’s annual consumption should derive from EU refining. Third-country supply shares for the block vary from 61% for aluminum to 100% for baryte, beryllium, and niobium. Moreover, the CRMA aspires to meet at least 15% of annual consumption through recycled minerals, but it seems unrealistic, as currently only 1% of the EU demand for rare minerals is satisfied through recycling. 50% of the remaining 12 minerals fail to achieve the target due to either being consumed or converted in the industrial process, or due to the absence of sufficient scrap quantities available to meet the rapidly rising demand.18 These facts rule out the potential of achieving self-sufficiency.19

Main EU Suppliers of Individual CRMs. Source: EU Commission (2023)20

On the basis of the above, a multitude of challenges derive, which bring clouds over the effectiveness of the Act. The prevailing question is whether alternative foreign suppliers are sufficient, given China’s undisputed dominant role in refining critical minerals. In particular, the country mines 72% of rare earth concentrates,21 processes 87%, and refines 91%. Plus, China produces 94% of the globe’s permanent magnets, which are essential for wind turbines and EV motors,22 while it owns 78% of the world’s EV battery manufacturing capacity and is also the base for three-fourths of lithium-ion battery megafactories.23 The above figures justify China’s former ruler Deng Xiaoping’s quote in 1987: "The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.” 24

The EU is actively seeking for alternative trade partners, including Australia, which accounts for 6% of the world’s rare earth mining production. But, with Australia resisting the EU’s request to eliminate export price controls on CRMs, the EU’s leverage appears constrained.25 Utilization of the US’ aspirations to form a domestic critical minerals supply chain is also an option.26 And even though CRMs can be found in abundancy around the West, mining projects are time-intensive, and face significant capital requirements, as well as regulatory and bureaucratic burdens.27

In the quest to attract vital private investments for Strategic Projects, the CRMA faces a budgetary shortfall. While the Commission suggests InvestEU as a solution through financial guarantees and debt products, this alone may not spark substantial investment without additional public resources. Relying solely on financial guarantees could backfire, risking construction setbacks, environmental compromises,28 and exclude smaller corporations from investment opportunities, emphasizing the urgency for substantive resources to effectively support the bloc’s CRMs value chain.

Moreover, the framework for Strategic Projects lacks a compelling investment pitch for businesses. While the CRMA focuses on expediting permitting to foster domestic extraction, speeding-up permitting procedures may not necessarily accelerate project development, as most delays occur during exploration and project preparation phases. Rushed permits could strain public consultation, and raise legal and environmental concerns, especially in remote or indigenous areas where fair consultation and compensation procedures require time. 29

Finally, what if decoupling efforts backfired and actually risked fragmenting global supply chains and consequently hampered decarbonization efforts? Examples include Canada and Australia's actions against Chinese investment in rare earth companies, which have prompted China to enforce export controls.30 For this reason, it seems wiser for the EU to not completely disconnect from Chinese bilateral relations, and instead pursue "de-risking” actions.

Greece’s Window of Opportunity

Greece holds impressive positions in the production of perlite (2nd largest producer globally), bentonite (4th), magnesite (9th), and bauxite (15th).31 Simultaneously, the country leads in global production of ferronickel and ranks prominently within the EU for both aluminum and alumina production.32 Its territory also boasts resources, such as gold, chromite, copper, dolomite, and feldspar, while the country also possesses substantial reserves of nickel, cobalt, and manganese, key components for the burgeoning EV battery industry.33 Other minerals include high-purity silicon, indium, tellurium, and gallium, essential for microchips, photovoltaics and wind turbines, with silicon extraction being already underway in the regions of Florina and Kozani. Such resources can also be identified in certain State-Mining Areas, demonstrating promising potential for rare earths.34 However, it should be noted that due to the absence of updated research οn reserve data, the actual extraction potential of the country has not yet been ascertained.

State Mining Areas of Greece, including Prefectures, Surface Areas, Minerals & Reserves35

Exploitation of Greece’s significant CRMs reserves can emerge the country as a major global producer with enhanced geopolitical influence, as well as a promoter of EU objectives. In fact, Greece may have the capability to transform itself into a European hub for the production and trade of certain critical minerals, since it’s one of the largest EU producers of bauxite, while the country’s potential in antimony and battery production elements has also caught the Union’s eye.

The domestic advantages of such an evolution can be plenty; the Greek mining sector accounts for approximately 3% of the country's GDP, while if the right conditions are met it can reach 5-6%, generate about 60,000-70,000 jobs, and mobilize investments of more than €500 million,36 further restoring the reputation of "Greece in crisis”. Greater access to CRMs will also give a push to this marathon of achieving the green energy transition. Attracting foreign investment capital will not only strengthen the existing mining infrastructure but will also bring the necessary know-how to optimize and make production processes sustainable, while upskilling the workforce.

But it’s a tough nut to crack! The Greek government must take seriously the management of certain roadblocks to reach the country’s full potential. Licensing and spatial planning for the exploration and extraction of minerals can be a headache, as bureaucratic procedures in Greece are very time-consuming, leading to significant delay of projects and lost revenue, which discourages potential investors. At the same time, the persistently high energy costs add further to mining costs, given the high energy requirements of the extraction and processing of minerals. Moreover, in the push for a green economy, there is a troubling downside: Mining practices can threaten ecosystems and the livelihoods of those reliant on them. This creates the social dilemma between accepting mining activity and protecting the natural environment,37 while keeping in mind that Greece does not yet have the necessary know-how and technology to promote green mining.

Next Steps

In this promising landscape, Greece needs to tick off a lengthy list of game-changing initiatives. Intensified exploration, improved regulatory framework for mining activities, sped up licensing procedures for access to deposits of strategic interest, 38 as well as promotion of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) are part of the essential toolkit to stimulate investment. European funding sources (e.g., from RePowerEU) can also enhance mining projects’ feasibility, while cooperation with other EU Member-States is deemed crucial, for the exchange of expertise in exploring, mining, and processing of CRMs.

Yet, amidst the flurry of advancement, one echo resonates loudly: harmonizing environmental stewardship and climate consciousness. This can be achieved by circular economy applications, implementation of green technologies during downstream activities, tighter investigations, stricter limits, and higher costs for carbon emissions. Such commitments will also facilitate social acceptance of mineral exploitation activities.39

The EU and Greece must seize the geopolitical opportunity of the energy transition in the greenest way, transforming the EU to a self-sufficient region in critical raw materials and bringing it closer to its green energy objectives, while highlighting Greece’s potential. This is where Greece can emerge not as a mere player, but as a luminary breaking the chains of outdated ideologies in exchange for a bold, innovative redefinition of its role.

References

- Mahmood, Jemilah, Douglas McCauley, and Mauricio Cárdenas. (2024). "Critical Minerals Are Key to the Energy Transition. What’s Needed Now.” World Economic Forum. January 15, 2024. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/energy-transition-critical-minerals-technology/.

- International Energy Agency. (2021). Executive Summary – the Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions – Analysis. IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary

- European Council. (2023, November 21). Infographic - An EU critical raw materials act for the future of EU supply chains [Review of Infographic - An EU critical raw materials act for the future of EU supply chains]. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/critical-raw-materials/

- Financial Times. Rare Earths. (2023, September 21). https://ig.ft.com/rare-earths/

- EU looks to Greece for niche metals | eKathimerini.com. (2023, July 16). https://www.ekathimerini.com/economy/1215482/eu-looks-to-greece-for-niche-metals/

- Melfos, V., & Voudouris, P. Ch. (2012). Geological, Mineralogical and Geochemical Aspects for Critical and Rare Metals in Greece. Minerals, 2(4), 300–317. https://doi.org/10.3390/min2040300

- Clean energy demand for critical minerals set to soar as the world pursues net zero goals - News - IEA. (2021, May 5). IEA. https://www.iea.org/news/clean-energy-demand-for-critical-minerals-set-to-soar-as-the-world-pursues-net-zero-goals

- IEA. Why the European Union needs bold and broad strategies for critical minerals – Analysis. https://www.iea.org/commentaries/why-the-european-union-needs-bold-and-broad-strategies-for-critical-minerals

- Reuters. (2023, April 4). Factbox: Economic reliance on China that EU wants to "rebalance.” https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/economic-reliance-china-that-eu-wants-rebalance-2023-04-04/

- European Union. European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA) @EU_ERMA #EUerma Rare Earth Magnets and Motors: A European Call for Action. https://eit.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021_09-24_ree_cluster_report2.pdf

- Our dependency on China for critical minerals is dangerous. (2024, January 8). Politics Home. https://www.politicshome.com/thehouse/article/dependency-china-critical-minerals-dangerous

- Nikkei Asia. $2.6tn could evaporate from global economy in Taiwan emergency. https://asia.nikkei.com/static/vdata/infographics/2-dot-6tn-dollars-could-evaporate-from-global-economy-in-taiwan-emergency/

- Faucon, W. B., Costas Paris and Benoit. Tesla to Halt Production in Germany as Red Sea Conflict Hits Supply Chains. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/business/tesla-to-halt-production-at-german-car-factory-as-red-sea-conflict-hits-supply-chains-3735e991

- The European Union can go green and lower dependencies on China | DIIS. (2024, February 21). https://www.diis.dk/en/research/the-european-union-can-go-green-and-lower-dependencies-on-china

- IMF. Geo-Economic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2023/01/11/Geo-Economic-Fragmentation-and-the-Future-of-Multilateralism-527266

- Banque de France. Critical raw materials: the dependence and vulnerabilities of the EU. https://www.banque-france.fr/en/publications-and-statistics/publications/critical-raw-materials-dependence-and-vulnerabilities-eu

- European Union. Critical Raw Materials Act. https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials/critical-raw-materials-act_en

- Allianz. (2023, August 1). Critical raw materials: Is Europe ready to go back to the future? https://www.allianz.com/content/dam/onemarketing/azcom/Allianz_com/economic-research/publications/specials/en/2023/august/01_08_2023-Critical-Raw-Materials.pdf

- Financial Times. Rare Earths. (2023, September 21). https://ig.ft.com/rare-earths/

- European Commission. (2023). Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU.

- USGS. (2024). U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries. https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2024/mcs2024-rare-earths.pdf

- Financial Times. Rare Earths. (2023, September 21). https://ig.ft.com/rare-earths/

- Pettitt, J. (2022, January 15). How the U.S. fell behind in lithium, the "white gold” of electric vehicles. CNBC. https://www.cnbc. com/2022/01/15/how-the-us-fell-way-behind- in-lithium-white-gold-for-evs.html

- Investigate Europe. (2023, October 26). Green transition, dirty business: Europe’s struggle to tear loose from Chinese minerals. Investigate Europe. https://www.investigate-europe.eu/posts/green-transition-mines-metals-minerals-china-europe

- Bruegel. (2023, September 15). The reason for the European Union-Australia trade negotiation hiccup. The Brussels-Based Economic Think Tank. https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/reason-european-union-australia-trade-negotiation-hiccup

- Financial Times. Rare Earths. (2023, September 21). https://ig.ft.com/rare-earths/

- Hiebert, K. (2023, November 27). The Fight Over Critical Minerals Has Just Begun. https://www.cigionline.org/articles/the-fight-over-critical-minerals-has-just-begun/

- Griffith-Jones, S., & Naqvi, N. (2021). Leveraging Policy Steer? Industrial Policy, Risk-Sharing, and the European Investment Bank. Oxford University Press EBooks, 90–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198859703.003.0004

- Wernert, Y., & Findeisen, F. (2023, June 30). Meeting the costs of resilience: The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Strategy must go the extra kilometer. Jacques Delors Centre. https://www.delorscentre.eu/en/publications/eu-critical-raw-materials

- Shi, X., & Shen, Y. (2023, November 7). Bifurcation in the Critical Minerals Market Could Throw off the Global Energy Transition. Thediplomat.com. https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/bifurcation-in-the-critical-minerals-market-could-throw-off-the-global-energy-transition/

- Reichl, C.; Schatz, M. Minerals Production, World Mining Data; Republic of Austria, Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Regions and Tourism: Vienna, Austria, 2020.

- Eliopoulos, D.G.; Economou-Eliopoulos, M. Geochemical and mineralogical characteristics of Fe-Ni- and bauxitic-laterite deposits of Greece. Ore Geol. Rev. 2000, 16, 41–58.

- 100 Years of Hellenic Geological Survey, Hellenic Survey of Geology and Mineral Exploration. 2021, pp. 160–163. Available online: https://eagme.gr/static-pages/100-xronia

- Committee for the Assessment of State Owned Mining and Industrial Minerals Areas Economic and Reserves Potential; Project Report; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2014.

- Lampou, D., Karathanasis, C., Zafeiratos, I. G., & Tzeferis, P. G. (2021). A Roadmap for Exploration and Exploitation of Mineral Raw Materials in Greece. International Conference on Raw Materials and Circular Economy. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2021005080

- Energy Press. (2023, July 31). Ευκαιρίες για τις εξορύξεις και τη μεταλλουργία στην Ελλάδα – Τι αλλαγές φέρνει το Critical Raw Material Act της ΕΕ και οι επενδύσεις της Mytilineos. Energypress.gr. https://energypress.gr/news/eykairies-gia-tis-exoryxeis-kai-ti-metalloyrgia-stin-ellada-ti-allages-fernei-critical-raw

- Strategic Dialogue on Sustainable Raw Materials for Europe. (2018, November 30). Towards New Paths of Raw Material Cooperation - Renewing EU Partnerships. https://www.stradeproject.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/STRADE_Final_Brochure_2018.pdf

- IOBE. (2022, November 22). The raw materials sector and the Greek economy. https://rcgreece.labmet.ntua.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Vettas_7th_Greek_Raw_Materials_Community_Dialogue_22112022.pdf

- Energy Press. (2023, July 31). Ευκαιρίες για τις εξορύξεις και τη μεταλλουργία στην Ελλάδα – Τι αλλαγές φέρνει το Critical Raw Material Act της ΕΕ και οι επενδύσεις της Mytilineos. Energypress.gr. https://energypress.gr/news/eykairies-gia-tis-exoryxeis-kai-ti-metalloyrgia-stin-ellada-ti-allages-fernei-critical-raw