On May 8, 2018, the United States withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), also known as the Iran nuclear deal, over concerns that the agreement was not comprehensive enough and failed to curtail Iran’s destabilizing activities across the Middle East.

To those who follow U.S. politics, such an outcome should not have come as a surprise. During the presidential campaign in 2016, then-candidate Donald Trump was vocal about his distaste, to put it mildly, for the Iranian regime, which he described on several occasions as the "leading state sponsor of terror.” More recently, President Trump described the agreement as a "horrible one-sided deal that should have never, ever been made.” He announced that the U.S. was withdrawing from it and that his administration was going to institute "the highest level of economic sanctions” on Iran.

This round of measures will come into full effect following 90-day and 180-day wind-down periods for activities involving Iran that were consistent with the U.S. sanctions relief specified in the JCPOA. In other words, the sanctions will apply in two waves: the first coming into force in August 2018 and the second in November 2018, with the latter primarily hitting the energy sector. Meanwhile, European Union leaders have vowed that they would try to salvage the nuclear agreement, though it remains unclear whether they can go it alone.

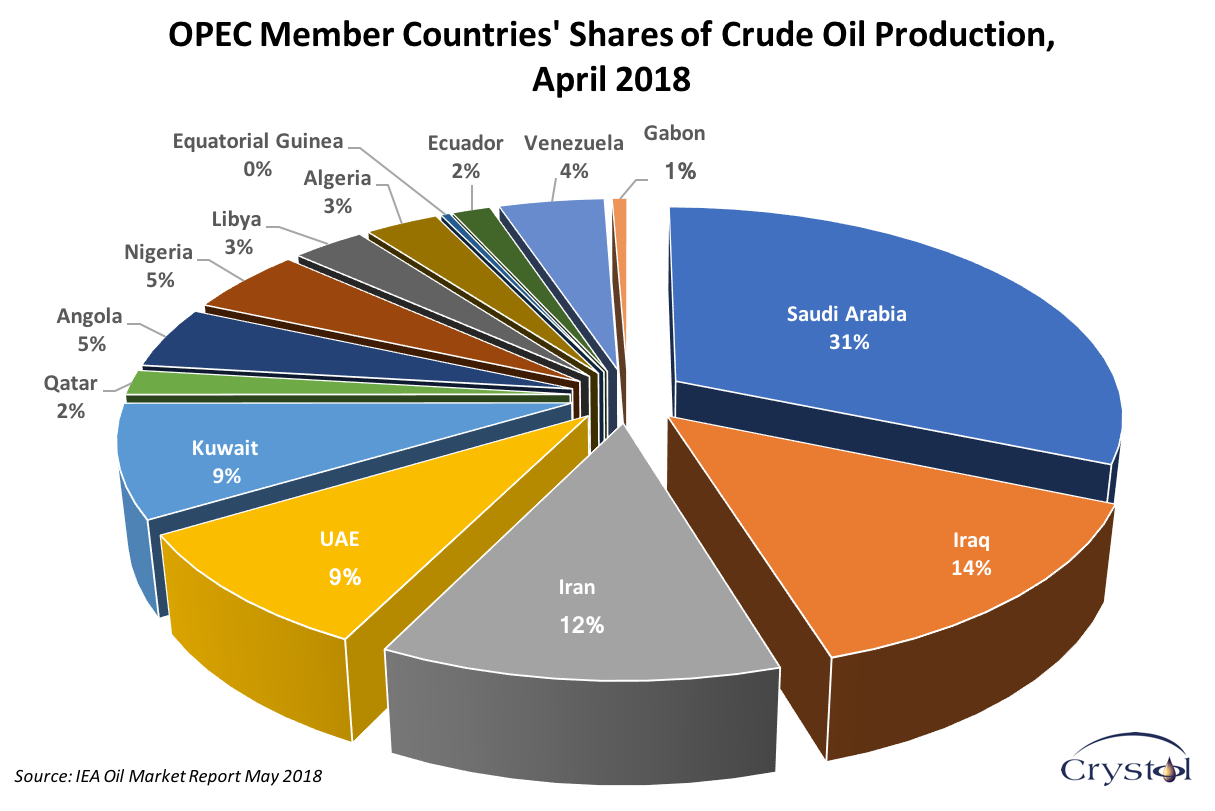

Given Iran’s importance as a major oil producer – the fourth in the world after the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Russia (according to BP Statistical Review of World Energy), and OPEC’s third largest producer after Saudi Arabia and Iraq – it is hard to overestimate the implications of this development on global oil markets.

Lessons from the past

A look back at when the sanctions were first imposed on Iran around 2012 and the events after they were lifted in 2016 can provide some insights into the unfolding situation.

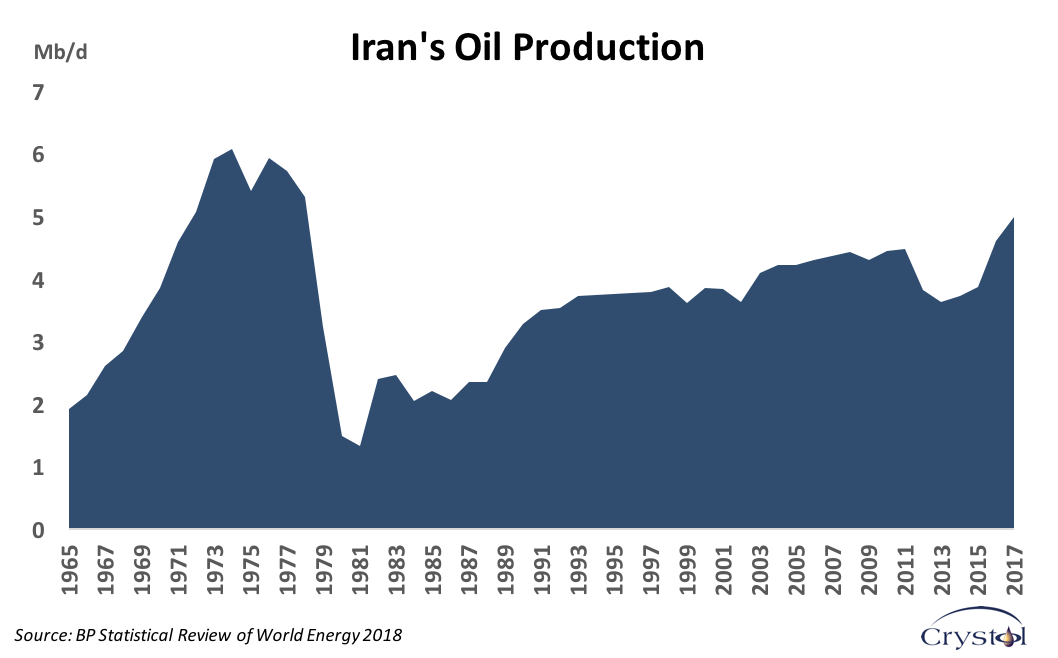

The U.S. and EU sanctions imposed in late 2011 and 2012 targeted the Iranian energy sector and, by 2015, effectively halved Iran’s oil exports. Production also suffered, as the sanctions limited international investment in Iran. The oil price during that period (up until the summer of 2014) hovered around $110 a barrel.

In 2015, the P5+1 (the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council – China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the U.S. – plus Germany) announced the JCPOA. Tehran agreed to limit its nuclear program in exchange for the lifting of the sanctions. Accordingly, on January 16, 2016, the economic and trade sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear program were lifted. The measure removed restrictions on Iran’s crude oil exports, which increased by more than 1 million barrels a day (mb/d) within a year and returned to their pre-sanctions level. The difference was that the commodity was selling at half the price of only a few years earlier.

What remained in place, however, were the U.S. secondary sanctions that limited Iran’s access to international banking services, thereby constraining processing payments to that country. As a result, the "bonanza” that both international investors and the Iranians expected to see in the country’s oil business did not materialize. International banks did not want to face the consequences of breaching U.S. rules.

Today, the situation looks more challenging, mainly because of the uncertainty that the return of the sanctions has created. European banks have already announced that it would be difficult to circumvent U.S. restrictions. And European energy companies, such as the French giant Total, which, in 2017, announced a multibillion gas deal in Iran, have publicly said that they will have to comply with the sanctions, partly given the restrictions that their banks and insurers have imposed on them, and partly because they do not want to endanger their business relationship with the U.S.

At the June 2018 OPEC meeting, Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh acknowledged that the U.S. sanctions were already being felt in Iran. According to S&P Global Platts, shipping companies, banks and insurers are already shying away from doing business with Tehran. Minister Zanganeh, however, added that his priority was to safeguard Iran’s oil exports. His answer may well point to Asia, which is the fastest growing center for oil demand in the world.

Asian companies, especially the Chinese, are unlikely to halt their oil purchases from Iran and may well take advantage of the situation to secure good deals, first in terms of increased oil imports at a discounted price, and secondly, in terms of direct investments in Iran should they achieve attractive terms. China’s CNPC, Total’s partner in Iran’s South Pars natural gas project, is ready to take over operations if the French giant withdraws. With the recent trade spat between Beijing and Washington, it is unlikely that China will show respect for the U.S.-made rules in the Middle East.

Risk premium

In its May 2018 Monthly Oil Market Report, the International Energy Agency argues that the current Iranian problem "has switched the focus of oil market analysis from the fundamentals to geopolitics.” Analysts currently refer to the geopolitical risk premium which is putting upward pressure on oil prices. That premium nearly disappears when the oil market is well supplied, as it was in the period between 2015 and 2017. Then, oil prices barely reacted to unrest and wars in major producing countries, such as Iraq, Libya, Venezuela or Yemen. In fact, it took the biggest alliance in the history of the oil industry – the so-called OPEC+ led by Saudi Arabia and Russia – to stop prices from falling.

When the market tightens, because, for example, growth in supplies does not keep up with an increase in demand, the oil price becomes more sensitive to political developments – especially if they affect major producers. Even before President Trump made public his decision about the Iran nuclear deal, oil prices seem to have reacted to the appointment of John Bolton as his national security advisor. Mr. Bolton has been a sharp critic of the nuclear agreement with Tehran and was a supporter of the Iraq war in 2003.

It is almost impossible to quantify the geopolitical risk premium or to state how much precisely it adds to the price of crude oil. What is clear, however, is that the uncertainty about Iran’s exports, which currently amount to 2.4 mb/d, combined with other uncertainties in the market, including supplies from Venezuela, which have been in freefall since 2016, are creating more unease in the market. That said, compared to a decade ago, the oil price’s reaction to geopolitical developments remains tame. In the past, any tension in the Middle East would send oil prices soaring.

Outlook

Four factors should be taken into consideration when assessing further market reaction to the current situation.

First, there is the time factor. It is unclear if between now and November 2018 the major buyers of Iranian oil, such as the EU, will be able to safeguard their purchases. The EU is yet to find a way to save the JCPOA and protect its companies from being exposed to U.S. penalties. The chances of that happening appear modest at this stage. If Iranian oil sales are reduced by half, as in 2015, then oil prices are likely to go up, all else being equal.

Second, the recent decision by OPEC+ to increase its output may ease the pressure on prices. The group, however, shied away from specifics and it is unclear how much more crude the organization and its allies will pump into the market, with different OPEC ministers giving varying estimates. It is also unclear whether the increase in output would be enough to compensate for potential losses from elsewhere, especially if Venezuelan production continues to deteriorate and Iranian oil exports are curtailed. There is, however, one strategic dimension to this scenario, and it explains Tehran’s discontent with the deal: countries such as Iran would lose market share to those that can increase production and exports, namely Saudi Arabia.

Then, two important mechanisms come into play. On one hand, demand’s reaction to prices – the two remain negatively correlated – and on the other, the U.S. tight oil response to prices, where the correlation is positive. Both imply that higher oil prices, if they result from the U.S. sanctions, are unlikely to be long-lived.